SOURCE: CNN.com Blogs

March 23rd, 2012

By Mimi Chakarova, Special to CNN

http://cnn.com/video/?/video/international/2012/03/23/price-of-sex-film-trafficking.cnn

For the past decade, photographer-filmmaker Mimi Chakarova has examined conflict, corruption and the sex trade. Her film "The Price of Sex," a feature-length documentary made over seven years on trafficking and corruption, premiered in 2011. She was awarded the Nestor Almendros Award for courage in filmmaking at the Human Rights Watch Film Festival in New York. It will air in the U.S. on The Documentary Channel on April 11 at 4.30p0.m. ET

She was wearing a polka dot skirt and her favorite pink flip-flops the day she left her village in Albania. Her mom called out her name before she got into her boyfriend's red Mitsubishi. She didn't turn to wave goodbye. She was 12 and angry.

Her stepdad has been raping her for as long as she can remember. She couldn't tell her mom. She knows she'd be sent away. She'd be the one blamed. Girls tempt grown men and bring it on themselves, they'd say. And there was also his drinking that made him do it, they'd add.

Once they were in Italy, her boyfriend changed - he told her she'll work for him as a prostitute. She thought he was playing some silly joke. She left home to be with him; to one day marry him. He is older. She's in love.

He slapped her back to reality. Told her how much money she cost him for the speedboat ride, her fake documents, the clothes and make-up he bought to make her look pretty and pass for 18.

She cried. And he cut her knee deep with a knife to make her stop. For the next seven years, the scar is a reminder she has no one but him to fear and return to.

Years later, I recorded her story at a secret shelter for women and saw court documents backing up what she told me. She pressed charges against her pimp but she says his uncle was a judge and released him on bail. The pimp left Albania until things cooled off. He is still free and has even bought a three-story house in her village in northern Albania.

Meanwhile, her family found out she was a "hooker who didn't even bring back any money, only an abortion and STDs." They disowned her. Her mom still doesn't know her husband was the first to abuse her.

That was the story of a young Albanian girl I met while filming "The Price of Sex" - sold into sex work in Italy and Belgium by a man who pretended to be her boyfriend.

The first woman I photographed had been trafficked to Turkey. She returned to Moldova, one of the poorest countries in Eastern Europe, wearing the same pants, blouse and shoes she left in.

Relying on her contacts in the town where she was sold, I retraced her journey to Turkey and met with one of her pimps - a man notorious for the sadistic abuse of the girls he owned.

Unable to take photographs, I posed as a Bulgarian woman for sale and spoke with Tania, a girl from Ukraine who was trafficked at the age of 23 and purchased as a slave by Yusuf.

I push my camera bag under the white plastic table, slouching down to appear more relaxed. The sun set four hours ago and the outdoor cafe where I'm sitting faces the fishing boats docked by the bay.

Only now the fear slowly seeps in as I notice a middle-aged man with an off-white cotton shirt and beige trousers approach the table.

The young woman by his side looks straight ahead. Her clothes are a few sizes too small by intent. They sit down at opposite ends of one another. I introduce myself in Russian.

The pimp doesn't understand but he doesn't need to. He is here to price me. He adjusts his gold-rimmed glasses, lights a cigarette and puts his cell phone on the table.

The young woman, Tatiana, also known as Tania, is average – small, tired and looking much older than 25.

We start talking. I'm nervous: "I am coming from Istanbul. For work."

"So you know what this is about?" she asks slowly as if speaking in code and then takes another drag on her cigarette.

"Yes."

"Let's talk then," she smiles at Yusuf who is staring at my breasts without trying to be discreet. "You'll live with him. There is plenty of work," she pauses to adjust the thick strap of her orange tank top. "Sometimes 30 a day."

She tells me the clients are handsome, she denies Yusuf hits her – though in both cases I know the truth.

"Look, Yusuf likes you," she says. "You can start tomorrow."

My hand is shaking as I try to write down the digits of Tania's cell phone number.

"It's your first time, huh?" Tania smiles. "I was the same, hadn't done this before. But after a couple of days, you'll forget everything," she pauses and pulls out another cigarette.

"Home, friends, memories... " she looks down and inhales the smoke. "Nothing will matter."

Tania stares into the distance where boat lights flicker. Her next client is waiting in one of these boats. "Think about it," she stands up. "We'll be back in a bit."

She walks away with Yusuf close by her side like a father or an older uncle.

Working to expose this misery makes you want to never leave your house again. But you can't hide. You've promised too many people to carry on. You've connected the dots for a decade. You can break it down into the most basic elements: supply and demand.

The supply is steady - poor women and kids need a way out. They leave in search of jobs. They are duped, sold, used up and deported back to where they came from. Penniless, ashamed, scared.

And the demand? It's something few are willing to tackle. It's not only fishermen, construction workers and soldiers who frequent the brothels of Turkey, Russia, Kosovo, the United Arab Emirates, the U.K., Israel, Greece, Italy and many other countries where women are trafficked to. You also have cops, politicians, policy makers, U.N. personnel. Men who'd rather remain anonymous.

And after all, this human trafficking phenomenon isn't a new criminal trend. It's existed since the beginning of documented time. But what is astonishing to me is how recently we agreed to agree that sex slavery should be punished by law.

Think about it. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime defined the Palermo Protocol in 2000 and implemented it in 2003. That's only nine years ago! And The Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act was passed by the U.S. Department of State in 2000.

Awareness matters. People must know. We must change perceptions.

But let's not fool ourselves. As long as the huge discrepancy between poor and rich countries continues to exist, as long as access to justice is denied or corrupt, as long as stigma keeps women silent, and law enforcement agents take bribes or use the trafficked women as bargaining chips, we can make films, go to schools, speak until our voices grow weak and still only make a pitiful dent.

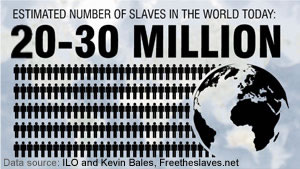

The first question we must answer is "Why is human trafficking only second to drugs in profitability?"

Then think of Henry Ford's words: "Show me who profits from war and I will show you how to stop the war."

Apply this to trafficking. If we, as an international community, agreed that the trafficking and selling of human beings is unacceptable and we've had nine years to reduce the numbers, then what else is standing in the way? Do the lives of poor women matter?

I am posing these questions because unless we honestly answer them, all of my work and the persistent effort and dedication of others in the field won't be enough in this lifetime.

And I don't think it is fair for the next generation should inherit one of the worst human rights abuses known to mankind. The time is now.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Mimi Chakarova.

No comments:

Post a Comment