Joshua Kors

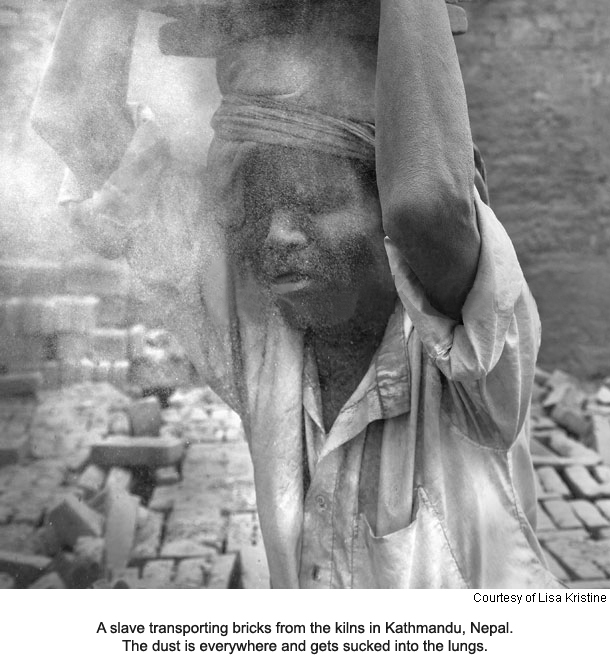

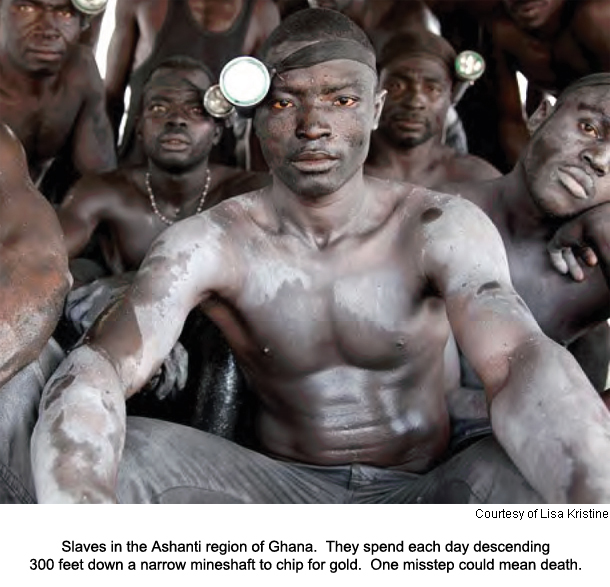

Posted: 8/26/11 03:35 PM ETThe most pernicious lie still taught in elementary school is that slavery ended in 1865 with the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment. The truth is more disturbing. Today, 146 years later, slavery is rampant, both in the U.S. and abroad. It lives in the dusty, pitch-black mine shafts of Ghana, where young men are sent to chip for gold, in the scorching brick kilns of India, where children spend endless hours lugging bricks, behind the hidden walls of San Francisco's massage parlors, where young girls are forced to perform sexual services.

According to the non-profit organization Free the Slaves, 27 million people are currently enslaved. Who are they? Lisa Kristine was determined to find out.

The acclaimed photographer spent a year traveling the world—from Ghana to India to Nepal—photographing slaves, recording their stories. Her new book, Slavery, presents those stories with hauntingly memorable images: the cracked, dried fingers of a young slave stricken with malaria, the glimmer in the eyes of an eight-year-old boy still hoping to be free.

The acclaimed photographer spent a year traveling the world—from Ghana to India to Nepal—photographing slaves, recording their stories. Her new book, Slavery, presents those stories with hauntingly memorable images: the cracked, dried fingers of a young slave stricken with malaria, the glimmer in the eyes of an eight-year-old boy still hoping to be free.

Kristine spoke with me about the people she met, the cruelty she witnessed, and what every reader can do to help bring slavery to an end.

Kors: In your first two books, A Human Thread and This Moment, you photograph the vibrant, joyous colors of indigenous people: warriors dancing in Papua New Guinea, young men in Thailand splashing around in a lake with elephants. Now slavery.

Kristine: Quite a contrast, isn't it?

Kors: It is. What got you interested?

Kristine: Well, I was presenting my photos at the Peace Summit in Vancouver when I was introduced to one of the founders of Free the Slaves. He said there are 27 million slaves in the world right now. That freaked me out. I've been to a lot of countries, and I never saw slavery. Did I overlook it? Did I not realize what I was seeing? Twenty-seven million people. The whole thing lit a fire under me that I just couldn't get rid of. Finally I bought a ticket to Los Angeles, met with the organization's directors and told them I wanted to step up. I wanted to tell these people's stories.

Kors: Tell me a little about Free the Slaves?

Kristine: They're an amazing organization with partners in India, Nepal, Ghana. Their work is going in and freeing people. Sometimes you have people who don't even know they are slaves, people working 16, 17 hours a day in awful conditions with no pay. This has been their whole lives, working all day breaking rocks or dyeing silk. They have nothing to compare it to. The organization comes in, gets them lawyers and a set-up where they can profit from their own work.

Kors: This is not a life people choose.

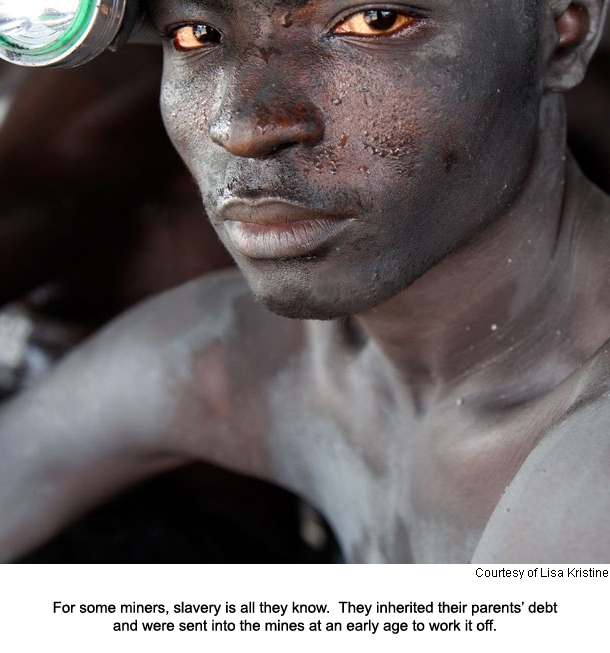

Kristine: Absolutely not. These are young men, boys, who are under threat of violence. They can't walk away. A lot of them are born into it based on their parents' debt. It's generation after generation.

Kors: Most people think slavery is over.

Kristine: (Kristine laughs.) I know. When people think of slavery, they think of an era from the distant past. Grainy photographs from Civil War times. And yet it goes on. The New York Times just did a chilling piece about sex slavery in Oakland. They reported that between 100,000 to 300,000 American children are sold into sex slavery every year. It's all around us. But people don't see it.

Kors: Maybe these photos can change that.

Kristine: I hope so. Because when people find out what's going on, their attitude changes. I've seen this issue light a fire under people the way it did with me.

Kors: You spent a year on this project.

Kristine: Yes, all 2010 in Nepal, Ghana, the brick kilns in India.

Kors: Tell me about those kilns.

Kristine: Oh, it was like walking into Dante's inferno: 120, 130 degrees. So hot that my camera would cease to function, and I couldn't touch it because the metal would burn my hands. The slaves would take the bricks from the kiln, stack the bricks on their heads, then load them to the trucks to be carted away. Most of the slaves were women, young girls. They were covered in dust, and it was constantly getting into their lungs.

Kors: Didn't you want to reach out to those girls and say, "I'm taking you with me." Or at least, "Here's $20. Pay off your debt. Now you can be free."

Kristine: Of course there's that urge. But I was given very strict instructions not to give any money, that that is not the way to create change. Think about the women who are taken from their families and forced into the sex industry. A raid come and frees you. You're rescued. Well, you're still separated from your family. You're stained with the social shame of having been a sex slave, and you have no education. Nobody's going to hire you to do anything else. Women freed under those circumstances slip back into slavery very quickly. ... What's needed is to give these women an education and a sense that they are human, that they deserve better.

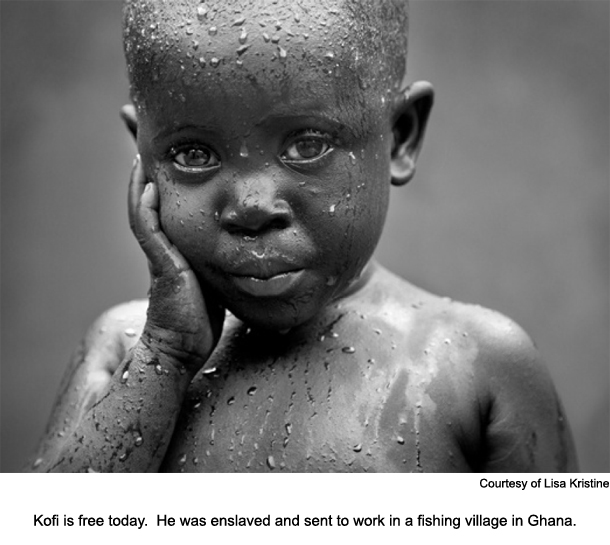

Kors: Looking at your photos, I kept thinking about the history textbooks I read in school and why those failed while your book succeeds. In the textbooks, slavery was an issue, an amorphous political problem. Your book is about real people—not an issue, but individuals. Like Kofi.

Kristine: Oh, Kofi. He's so cute, isn't he?

Kors: He is. Tell me about him.

Kristine: A man had come to his family's home, told his parents, "We'd like to bring your son to a wonderful school, give him a great education." The broker takes the son, sells him to the slave owners at Lake Volta, then disappears. Lake Volta, in the Brong Ahafo region of Ghana, is the largest man-made lake in the world. Children are stolen from all over to work in the lake, heading out in boats, dragging back nets filled with fish that weigh over 1,000 pounds. The nets often get tangled, so the slave owners will throw the children overboard to untangle the nets. Few of the children know how to swim. Every child I met knew another slave who had drowned.

Kors: But Kofi is recovering.

Kristine: Yes, he was rescued by a partner of Free the Slaves. I met him at a shelter, and he spent a lot of time bouncing on my knee. He has now been reunited with his parents. I think he's going to be fine.

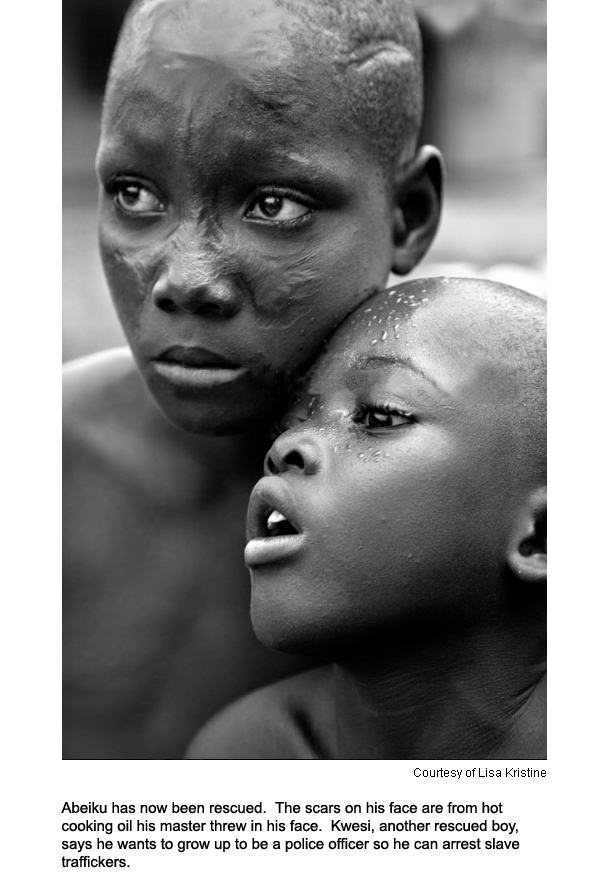

Kors: Abeiku is also free.

Kristine: Yes, though you can still see the scars on Abeiku's face. His owner threw hot cooking oil onto his face, punishment for speaking up. He had been beaten severely for many years before being rescued. For a long time at the shelter, he wouldn't talk. He had been raped. And at the shelter, they had to separate him from the other kids after he tried to be aggressively sexual.

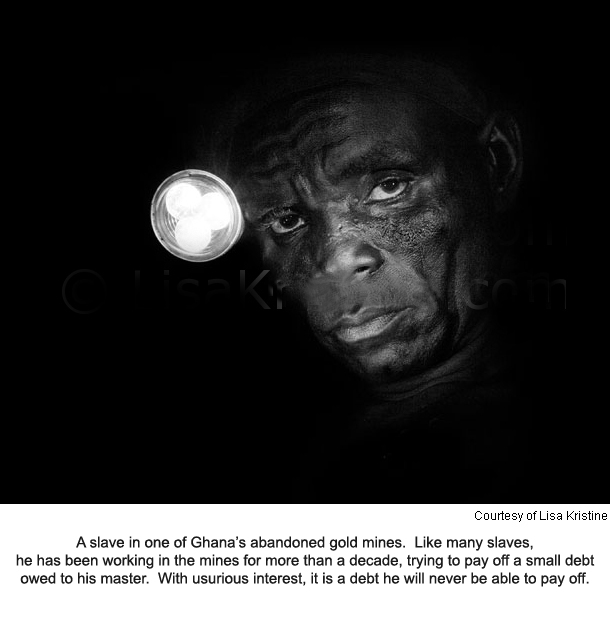

Kors: Most of the people in your photos are still enslaved. I think of that miner, looking into the camera, those sad, deadened eyes surrounded by darkness.

Kristine: I remember taking that photo. That miner, he was 44 years old. Been working down in the mine shaft for 15 years. When the gold rush occurred, people from all over Ghana came storming in, thinking this was their break. They were going to make it rich. Brokers come in and say, "I'll give you $70. You come work at my mine, and you can pay me back." The men sign their names, and now, with the massive interest, they have a debt they can never pay off.

Kors: These are illegal mines.

Kristine: Right. These are mines that have been shut down and abandoned. Most of the gold has already been extracted. And because they're illegal, if any of the miners get caught by police, they'll get arrested. ... Just photographing it was a dangerous operation. We got in a van, which headed into the jungle. Soon as we stepped out, the van disappeared. We cut a long, winding path through the jungle, wading through rivers that were waist-high, until we reached canyon with hundreds of slaves. There was a quarry with these mineshafts. I took my camera and crawled in. The shaft was three feet by three feet, extending hundreds of feet into the ground. It was pitch black, there's no oxygen pumped down there, and it is was hot. Some of the slaves stay down there for 24, 48, 72 hours at a time. And when they come up, they're holding a sack loaded with rocks, climbing the shaft's ladder, rung by rung, with one hand.

Kors: You must have been scared out of your mind.

Kristine: (Kristine exhales.) It's strange. I should have been but I wasn't. ... As I descended, I had one hand on my camera, the other on the rungs of the ladder. I could feel my hand slipping. And if you fall, you're dead. There are no safety mechanisms down there. It was dark and eerie, like descending into The Twilight Zone. ... I think part of my calm was the men I was with. Manuru especially. He has been in the mines for 10 years, since he was 9 years old. That's when his father died. His uncle then took him and headed to the mines. After a few years of mining, his uncle died of a lung disease, like a lot of the miners. Now it's just him.

Kors: Let me say something offensive that many readers might secretly be thinking. They're thinking, "Look, it's sad that slavery still exists. But the photos in her book are all from other countries. Most of the slaves are black. And a lot of the pics were taken in Africa, which is basically an unfixable disaster. I can't really do anything about it anyway. So I'm turning on Jersey Shore."

Kristine: Right. "It's them, not us. Who cares?" I think it's very easy to turn your head away from something troubling like this, to dismiss it and say, "These people are separate from us." But they're not. The stones in your driveway may have come from the slaves who spend all day breaking rocks because it's cheaper for the company to get them from India, where the labor is free. We are all connected. And we all have human value. That's what my work is about.

Kors: But do you think there's a racial component here? Jaycee Lee Dugard was essentially enslaved, and the public reaction was ferocious. The slavery of these people: virtual silence.

Kristine: I think everyone saw Jaycee as the girl next door. People freaked out thinking this had happened in the suburbs, in their own backyard. I don't know if they related to her because she was white.

Kors: Maybe not. I just wondered if you had thought about these racial issues, especially since your children were adopted from abroad.

Kristine: That's right. My son, who is five, was adopted from Ethiopia. My daughter was adopted from Guatemala. Her parents died of typhoid and malaria. We got her from an orphanage. They are the lights of my life.

Kors: When you met the boys in the gold mines of Ghana and the girls lugging stones in Nepal, did you think, this could have been my son. This could have been my daughter.

Kristine: I thought, this could have been anyone's son and anyone's daughter. Under different circumstances, this could have been me.

Kors: What makes your photos so amazing is the way you capture the eyes: the hope, the pain, the anger, sorrow and eventually, after years of captivity, a vacant, dead expression. Kevin Bales and Jolene Smith, co-founders of Free the Slaves, say it best in the intro to your book: "The eyes are the last part of a person to be devoured by slavery."

Kristine: It's true. After a few years, their eyes glaze over, and the light dims, as if their soul is turning off. From the eyes alone, you can almost tell how many years they've been enslaved.

Kors: I'm wondering if you saw the documentary War Photographer, a stunning film about acclaimed photojournalist James Nachtwey.

Kristine: I did see it. Nachtwey is one of my favorites.

Kors: Well, he says something in that film that really stayed with me. He says, "If war is an attempt to negate humanity, then photography can be perceived as the opposite of war."

Kristine: It can. Absolutely it can. Of course, it depends on who's holding the lens. I didn't come to Ghana to document horrors for their own sake. I came to show that these children still had dignity—and to put that on film.

Kors: Do you consider yourself a journalist?

Kristine: No, I don't. I see myself as a witness to humanity.

Kors: Have any of the slaves seen the photos?

Kristine: Not yet. I gathered some of the photos and will be sending them back in packages. But it's tricky. If these pictures fall into the wrong hands, there could be severe consequences. If a slave holder sees them, some of the children could be hurt.

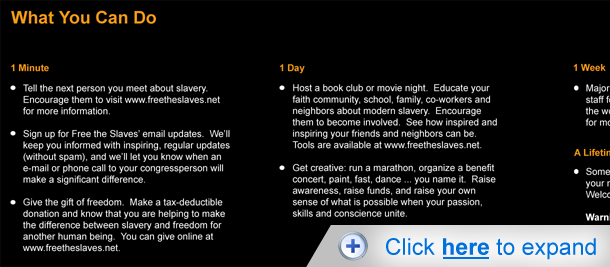

Kors: I love that at the end of your book, there's an entire page devoted to easy ways readers can make a difference: in a minute, with a day, by devoting a week, or a lifetime. Because even readers horrified by these photos will say, "But what can I do?"

Kristine: And the truth is, we can make a difference. Each of us has a lot more power than we think.

Kors: I love the warning under the "Devoting a Lifetime" section: "Warning: your life may become filled with meaning."

Kristine: (Kristine laughs.) That's right. This is a book about hope. People will look into Kofi's eyes, see the water droplets on his forehead, the hint of a smile, and realize that after being liberated, there is a positive future waiting for him. This is a book about what's possible. ... But we can't just wish an awful thing away. We have to make it happen.

Source: The Huffington Post

No comments:

Post a Comment